To what extent is historic and modern day 21st century design influenced by patriarchy?

Are we really welcome in the world around us as women?

‘Patriarch’, like ‘matriarch’, refers to the traditional male leader of a family. The decision maker. Some may say ruler (under any circumstance). The oldest male family member, and therefore bestowed with the most power. However, this traditional definition of the word has evolved, becoming more than just a family member’s title. Most would be more accustomed to the word ‘patriarchy’; evidently derived from the former; as the arguably outdated social construct in which ‘a society [is] controlled by men in which they use their power to their own advantage’ (Cambridge Dictionary, 2021). We hear the word ‘patriarchy’ thrown around a lot these days. For those of us who do not benefit, the word serves as a synonym to our society. As James Brown once famously sang, ‘this is a man’s world’.

Our voices as women may be heard a little louder than they were fifty or a hundred years ago, but they are reduced to mere whispers beside the bellowing words of men in our world. My fifteen year old self did not feel out-shouted when she spoke her mind. A school of not-always-likeminded girls was not necessarily a quiet environment, but it was conducive to young women’s voices being heard. The moment I left that school and entered the real world, a cold shock of truth splashed over me: I no longer held an equal stake in a conversation. If I wanted to have my wn educated opinions heard even when faced with an uneducated standpoint on the topic at hand, I would need to speak louder and articulate 50% more reasoning for my views against my male counterparts. In my school I debated with an arsenal of knowledge and was respected in my opinion; now I debate with an arsenal of volume and proof, and am hardly respected in my gender. I never had to whisper when in a bubble of women, yet in a world of half men and half women, I feel the need to shout.

Becoming increasingly well-read in history sheds light on just how long women have been the universally determined as holding less worth than men. Undoubtedly, this attitude has been passed from generation to generation as simply as the English language has, it’s just the way it is. The sentiment of the extreme privilege that women feel to be born in a time where we can buy our own houses, and have our ownbank accounts, vote for our political leaders and work in the same challenging roles that men can, is almost too heartbreaking to accept. Privileged to vote from a list of people that do not represent the population based on gender, let alone public opinion; privileged to work alongside men in the same roles as them, and get paid less. Learning about what happened hundreds of years ago may provide us with a sense of gratitude for our current positions in society, but we are still living in a world that was not designed with us in mind.

Historically a woman’s place was in the kitchen, here she worked hard, but she was most assuredly not anywhere near the stereotypical workplace. While in medieval rural Britain (1066-1485), most women worked the land with their male counterparts, they were paid less, and had no control over their own lives. Although they could earn a little money, they could not marry without the consent of their parents, and were often kept at home to work for the family for as long as possible before being married off (Trueman C., 2015). However, Tudor women are said to have had a very repressed life; ‘[they] were expected to support their husbands in their businesses or work, run their households and bear children’ (Mason E., 2019). Although it seems in mediaeval times women were working to some extent, it was still only to benefit the patriarchy; the men in their household who they had to cater to. They were usable assets of their fathers, husbands, brothers.

In current western society it is considered normal and fully acceptable for a woman to have a job in almost any sector, however the design sector is dominated by our male counterparts. It was not common practice for women to be accepted into design institutions until as recent as the 1920s, in response to the most progressive of colleges finally allowing women to study; like the Bauhaus in 1919 (Dawood S., 2018). In her article Women Design: The book challenging a ‘patriarchal industry’, Sarah Dawood delves into statistics about the design industry, and praises Libby Sellers for her book Women Design.

A study in 2013 found that while over 60% of students studying in the design sector were women, less than a third of the professional industry was actually made up of women. This suggests that even though women are trying to break into the design field, their male peers already seem to have an advantage. If these students (both male and female) are being taught n the same institutions and are leaving them with the same certificates, why do the statistics reflect a negatively skewed set of data towards women and their employment in the industry? In a 2018 report, the Architects Council of Europe stated that of registered architects, 74% were male and 26% female (France + Associates, 2020). There is a distinct disconnect between education and employment in the design field in terms of gender.

While women are now considered accepted into the workplace in the western world, are they actually welcome? The expanse between these two words and their definitions is deceptive, in fact some may argue that they represent the same meaning. In this instance ‘accepted’ is defined as tolerance, while ‘welcomed’ is defined as gladly received.

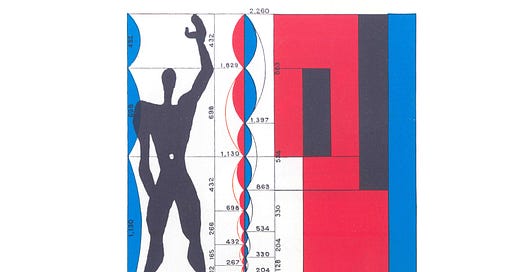

It is subtle, but the world in which we live in architecturally is quite literally built for men. Le Corbusier is of course an extremely famous name in the design world, and he set many precedents for the future of architectural design, as well as multiple other design strategies. However in his influence, Le Corbusier perhaps unintentionally created a world catered to a 6 foot tall man through his inception of his Le Modulor proportional system. Much of the postwar world (from a design perspective) was then ‘dictated’ as this in order ‘to make everything as convenient as possible for this 6ft-tall ideal man’ (Wainwright O., 2021). Le Modulor was a standard created by Le Corbusier as a central scale between Imperial and Metric scales. It considers the standard human height to be 1.83m and pruposefully excludes female heights in that assumption. Le Corbusier then went on to design buildings off of his own standard drawing in doors, kitchens, lightswitches and doorhandles to sit at the perfect level for a 6ft tall person to make their way around a building at the utmost ease. Of course this standard does not even represent the majority of the male population equally, let alone the female population. In 1950, if taking the average height of 30 year old men, the French average was 1.69m, while in the United Kingdom it was 1.71m; even when the standard was published in 1948 it was not truly representative of the male average. When using the same controls, the female averages were 1.58m in France, and 1.57m (Baten and Blum 2015) in the United Kingdom. How, then, did this measure become the basis for standard architectural dimensions and fitting placements?

In his article Why are our cities built for 6ft-tall men? The female architects who fought back, for The Guardian, Oliver Wainwright details how women were not passive throughout these confinements. A group of women wrote ‘the Matrix Feminism Design Co-operative’ in 1981, in which they claimed there is a lack of ‘“women’s tradition” in building design’. They also stated that ‘buildings do not control our lives. They reflect the dominant values in our society, political and architectural views, people’s demands and the constraints of finance, but we can live in them in different ways from those originally intended. Buildings only affect us in so much as they contain ideas about women, about our ‘proper place’, about what is private and what is public activity, about which things should be kept separate and which put together’ (Matrix Organisation, 1984) in Making Space: Women and the Man-made Environment.Upon reflection, this particular notion remains reasonably sincere in our current society. While we may not be able to change every building that was created with only men in mind, we can accept it to the point of living and working in these structures, while simultaneously knowing and acknowledging that women are accepted in these places in today’s society, however they may never have been intended to be present in such locations.

The extent of this acceptance is staggering four decades later, rather that there are not enough advocates within the professional design sphere in which to push female prioritising design in a patriarchal conglomerate. In reference to the aforementioned statistic, if the average percentage of female architects within the Architects Council of Europe’s study is merely 26%; equal representation within architecture is at a 4 to 1 disadvantage right at the very start. The blatant patriarchy within architecture specifically, is an issue which is overlooked daily by the majority of the population, while they remain in their male-built, male-designed, male-intended houses and workplaces.

After the organisation had run for 13 years, the Matrix Feminism Design Co-operative disbanded, but remain in the public eye in the form of adopting a section of the Barbican, London for a display. While this organisation has been pinnacle in women’s confidence to speak and write on the topic, arguably there has not been much development in the patriarchy of architecture, seeing as the issues which the Matrix group raised are still relevant to women globally today.

In order to build a comprehensive perspective of the impact of patriarchy within the design world, other forms must be studied. Furniture design is interesting from the sentiment of feminism, as Li Wanjun and Yang Li discover in their study of The embodiment of the female body in furniture design. Wanjun and Li discuss the stereotypical female connotations, as contrasting as they are, either delicate and sensitive, or an object of desire and sexuality for male gain. They state that within furniture design, ‘the female body is presented in an explicit or implicit way’ (Wanjun, Li, 2019). This is decided for the woman, presenting a show of power from a male perspective, furthermore illustrating the patriarchal relationship between man and woman in a design setting. As formerly stated, one of the stereotypical connotations listed by Wanjun and Li was females being an object of desire. Patriarchy is also defined as a male supremacy over his family/group/clan (Merriam-Webster, 2019), and supremacy in turn is interpreted as the highest authority or greatest power (Cambridge Dictionary, 2023). Therefore, presenting women who inform the design of furniture as so-called objects of desire, belittles them. It belittles them to a non-personified, inanimate creation; this creates a patriarchal concept, as a man uses his power over the model (a woman) to increase his cumulative power by belittling her, while simultaneously benefiting himself financially.

In reference to the study of the extent, both 21st century and historical design has been influenced by patriarchy, the findings presented imply that while patriarchy has not necessarily informed design to the fullest extent, it has had a paramount impact on some aspects of design, especially architecture, where it seems there may not be a change in male lead architectural designing as a result of the reflective statistics from the Architects Council of Europe, where there are more male architects than female by a staggering majority. In reflection of historical patriarchy towards women, much has definitely changed, however the patriarchy still exists in a strong, and sometimes poisonous fashion, globally today. In order for this to change, there must be respect for previous designers like Le Corbusier, and organisations such as the Matrix of Feminism Design Co-operative, but also a proactive willingness to change and listen to others who may raise issues, all the while noticing these day to day confinements of patriarchy, personally. Only then will the design world begin to cater to both men and women, and work towards an equilibrium of patriarchy and matriarchy (feminism). There also should be adaptations to the current process of design prospects, ensuring that gender and job prospects are on a directly proportional scale to one another, rather than favouring one gender. Finally, design as a programme has been historically and is still currently extensively influenced by patriarchy, with much of this power laying in the firm grasp of historic patriarchal influence from generation to generation.

Reference List

Associates, F. (2020). Architecture and Construction: No longer a. [online] France + Associates. Available at: https://www.franceandassociates.co.uk/thoughts-and-insights/architecture-and-construction-no-longer-a-man-made-profession .

Cambridge Dictionary (2021). PATRIARCHY | meaning in the Cambridge English Dictionary. [online] dictionary.cambridge.org. Available at: https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/patriarchy.

Cambridge Dictionary (2023). supremacy. [online] @CambridgeWords. Available at: https://dictionary.cambridge.org/us/dictionary/english/supremacy .

Dawood, S. (2018). Women Design: the book challenging a ‘patriarchal industry’. [online] Design Week. Available at: https://www.designweek.co.uk/issues/4-10-june-2018/women-design-libby-sellers-book-challenging-patriarchal-industry/.

Li, W. and Yang, L. (2019). The Embodiment of Female Body in Furniture Design. [online] Available at: https://www.atlantis-press.com/article/125923411.pdf .

Mason, E. (2019). Tudor women: what was life like? [online] History Extra. Available at: https://www.historyextra.com/period/tudor/tudor-women-what-was-life-like/.

Merriam-Webster (2019). Definition of PATRIARCHY. [online] Merriam-webster.com. Available at: https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/patriarchy.

Trueman, C. (2015). Medieval Women. [online] History Learning Site. Available at: https://www.historylearningsite.co.uk/medieval-england/medieval-women/.

Wainwright, O. (2021). Why are our cities built for 6ft-tall men? The female architects who fought back. [online] The Guardian. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2021/may/19/why-are-our-cities-built-for-6ft-tall-men-the-female-architects-who-fought-back.

Baten and Blum (2015). Our World in Data [online] OurWorldinData.org. Available at: https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/average-height-of-men-by-year-of-birth?time=1900..1980&facet=none&country=FRA~GBR~USA.

Figure 1: Baten and Blum (2015). Our World in Data [online] OurWorldinData.org. Available at: https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/average-height-of-men-by-year-of-birth?time=1900..1980&facet=none&country=FRA~GBR~USA.

As always, thank you for reading! This post is completely different to my others; it is a revisited essay from two years ago. The topic is something that I am still passionate about now, and it felt like the right time to give it a re-read and add a few little pieces in here and there.